The Navajo Nation's Response to The Big Cough

Mia

Throughout the past centuries, illnesses and pandemics have been recorded and documented, displaying detrimental losses to countries and communities, and being remembered for both the pain and death they cause, but also the medical advancements that can result from them. Today, we see this ringing just as true with the Covid-19 pandemic, and while it has caused many tragic losses across the globe, it has furthered research and advancements into amazing mRNA vaccines. However, when it comes to the pandemic, and many other medical instances, some groups of people are not given the same level of priority and are hit much harder by the effects of illness. Unfortunately, many of these groups are marginalized groups, like disabled people, people below the poverty line, third world countries, people of colour, and- focused on in this article- Indigenous people.

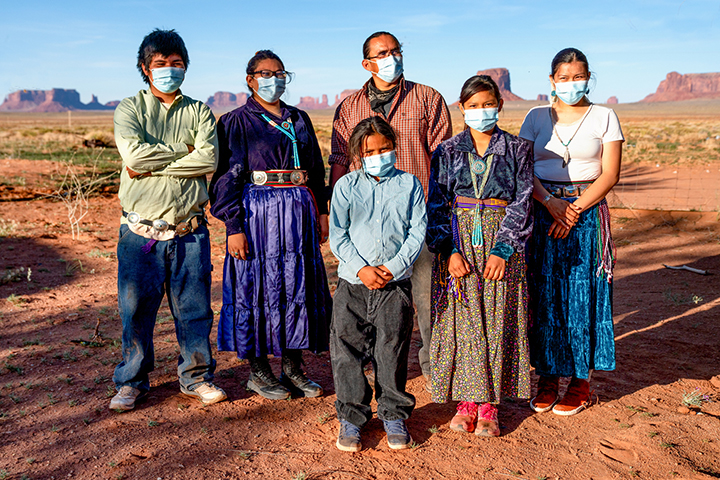

Cast Aside- The Navajo Nation

The Navajo Nation, which is home to over 175,000 Indigenous people and spreads over New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, has been hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic. As of June 11th, 30,914 positive cases have been confirmed within the Navajo Nation, and over 1,334 have passed due to Covid-19. While these numbers may seem minuscule to some in comparison to global numbers, Navajo Nation currently has an infection rate higher than New York’s- which used to be one of the most hot-spot states in the United States, as well as accounting for less than one-tenth of New Mexico’s population yet 55% of their recorded Covid-19 cases. More so, these are especially large numbers for their communities and face the possibility of growing even higher due to their already unfair circumstances- 40% of all Navajo people do not have access to running water in their homes, and 10% of all Navajo people do not have access to electricity. How can this be seen in any way as ethical or sustainable? If it seems like the odds are stacked against the Navajo people, it's because they are. Factors like access to clean drinking water, local hospitals, affordable food, adequate housing, medical malpractice, racism, and years of generational trauma which oftentimes results in alcohol abuse, sexual abuse, and poverty in Indigenous communities are just some of the factors which actively keep nations just like the Navajo nation oppressed and far less advantaged than those with colonial roots. Ultimately the former factors all stem from colonization and the horrors incurred on Indigenous people during the time of settlers “discovering” now stolen land, as well as the way colonization has shaped the governments view of Indigenous people, and how they treat them- in most cases, inhumanely. The Navajo people, as well as many other Indigenous nations, have been historically oppressed by forms of government across the world, and while the United States government once pledged in historic treaties that they would let Indigenous nations in their country self-govern and have sovereignty yet also provide a safeguard, essential resources, and essential services- they have completely abandoned this promise during not only Covid-19, but many other diseases, pandemics, and epidemics throughout history.

The Weaponization of Illnesses- Historical Indigenous Deaths

Illnesses, pathogens, and pandemics have been used in a war of medical warfare against Indigenous people just like the Navajo Nation, but it goes much farther back than the Covid-19 pandemic. It all began when French settlers in the early 17th century came to what is now Canada, bringing the variola virus with them, which would eventually turn into smallpox. This was something Indigenous people had never encountered before- frankly, Indigenous people had not seen many diseases before and hence had no immunity or tolerance built up in their immune systems. The effects of smallpox were detrimental on Indigenous people, and some reports say that around 95% of all Indigenous people living in Canada died due to the rapidly spreading virus, which unfortunately had not had its own vaccine invented at that point. Disease became something Indigenous people grew accustomed to and built some sense of immunity against, until the early 20th century. The 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic hit the world extremely hard, but hit Indigenous people even harder, as they were already in the process of being assimilated into settler culture, including residential schools. These schools were a hotbed for the flu, and as more and more Indigenous children were snatched from their families and brought to the schools, the virus was brought with them and infected hundreds of Indigenous children at each school. No Indigenous child was safe- they were used to help care for the sick instead of bringing in white nurses and doctors- and tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of Indigenous men, women, and children were among the millions killed in 1918. Can you imagine if your high school required you to care for ill students within the school who were suffering from something that was wiping out millions across the world? It seems ludicrous, but this was sadly the reality for many Indigenous children. While the over-a-century old case of influenza may seem like an outdated example, it was actually a predictor of future illnesses which would disproportionately affect Indigenous communities across the globe. Modern examples include not only the Covid-19 pandemic but the H1N1 influenza- more famously known as the ‘Swine Flu’ pandemic, which lasted from January 2009 until August 2010. The Swine Flu killed anywhere from 150,000-575,000 people across the globe, with Canada, the United States, and Mexico being hit the hardest out of countries, with 16.8% of all cases requiring intensive care in hospitals- and of all those infected and sent to intensive care, with Indigenous people being 6.5 times more likely to end up in intensive care units due to factors such as poor housing, not enough access to water and food, and most importantly- disgustingly inadequate healthcare.

A “Lose-Lose” Situation- Inaccessibility And Inequality In Healthcare

The Navajo Nation historically has had the odds stacked against them when it comes to healthcare and accessing it. With their economic status and lack of resources needed to survive, such as clean water, affordable food, and adequate housing, they have historically been hit the hardest by illnesses and viruses. But one of the most prominent factors for Indigenous nations like the Navajo, both in the United States, Canada, and many other countries across the globe, is that healthcare is not publicly accessible on many reserves and receives little to no proper funding from the government. This has been the case for many years, but it became broadcasted to the world on a larger scale during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic- and for the Navajo Nation, inaccessible healthcare meant taking matters into their own hands. Many Navajo healthcare workers and frontline workers have been working diligently to get the eligible population vaccinated, and as of May 26th, 2021, seventy percent of the Navajo nation is fully vaccinated. However, this comes at their own expense, as their frontline workers and representatives have had to work hard to secure vaccines, community and crowdfund their Covid-19 relief efforts, and encourage other Navajo people to take the jab. This is because it was believed that many Indigenous people would be hesitant to receive the vaccine, especially after the many historical episodes of weaponized illnesses and government ignorance, the most infamous being the smallpox epidemic which was brought over to Indigenous lands by colonizers and resulted in a staggering 95% of the Indigenous population at the time being wiped out. Some non-Indigenous Canadians have been hesitant as well, but not for the same reasons- can you imagine your own anxiety surrounding a vaccine if you had faced the same historical illness-based genocide? The Indian Health Service and many other Indigenous health clinics and providers within the Navajo Nation have been long underfunded by the United States government, but nothing changed once Covid-19 hit. This forced medical facilities to reuse protective gear, like gloves, masks, and medical equipment, as well as delayed transfers to larger, state-funded hospitals as Navajo people were dying at such alarming rates, there was far less urgency in flying them to other locations to better treat them. However, the pain of suffering from the Big Cough, as many Navajo residents call it, and the pain of watching a loved one suffer from it, do not stop at Navajo and other Indigenous health clinics. This is because Indigenous people are not much safer in state-funded, non-Indigenous-run hospitals, and unfortunately, we have seen this time and time again when it comes to suspicious Indigenous deaths and medical malpractice. Two of the most infamous cases actually come out of Canada, involving the death of an Indigenous woman and the nonconsensual sterilization of Indigenous girls- as young as nine years old.

In The Spirit of Reconciliation and Respect- Canadian Connection

The untimely and suspicious death of Joyce Echaquan, of the Atikamekw nation in Quebec, was a case that shocked Canada and opened the eyes of non-Indigenous Canadians to the horrors that Indigenous people face within hospitals- what was once thought to be a matter of less urgency when providing services or casual racism (which is still not at all acceptable), now became a matter of life and death. After Joyce was hospitalized for stomach pains, she was mistreated by nurses and eventually died of heart failure- but not before live-streaming her death on Facebook, in which nurses insulted her, called her slurs and even told Joyce at one point that she was “stupid as hell.” All this happened even while Joyce was live streaming on top of her calling for help and screaming in distress and fear, which shows that non-Indigenous healthcare professionals and providers have been taught to not only enforce these racist views but also ignore them when it happens in their workplaces. However- death is not the only thing ignored by and even allowed to slide within hospitals, as the sterilization of Indigenous girls under the age of ten has now come to light amid the growing conversation around Indigenous people in Canada. It started with a tweet from a Metis lawyer and activist named Breen Ouellette, who discussed how within the last decade, social workers have been forcing Indigenous girls to have IUD- a form of birth control- inserted by doctors to prevent pregnancy as a result of sexual abuse in the foster care system, and to top it off, did not provide the proper follow-up care. While the investigation into this act of eugenics and genocidal behaviour is ongoing, this is not the first time non-Indigenous health facilities and practitioners in Canada have been accused of forced sterilization- as this has been an ongoing practice since the early times of colonization. The question that many non-Indigenous Canadians have, and one you may have as well, is what is the bigger meaning to all this? The acts of discrimination, racism, sterilization, ignorance, and even downright murder that happen to Indigenous communities and people across the world, and especially in the United States and Canada, come back to the lack of accountability the governments take, and how little they value and respect Indigenous lives. This is ironic because the governments, especially the Canadian government, claim that they stand with Indigenous residential school survivors, Indigenous families affected by the clean drinking water problem, Indigenous communities impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, and so on- yet also refuse to address and more importantly, solve systemic issues such as medical discrimination, the weaponization of illnesses, forced sterilization, underfunded healthcare, sexual abuse in the foster care and judicial systems, and mental health crises on reserves and in Indigenous communities. The Canadian government refuses to listen to Indigenous people or support their communities but pretends like it is making leaps and bounds towards reconciliation and respect by doing the bare minimum- like accelerating vaccine doses for Indigenous people, creating a ‘land acknowledgement’ to play before the national anthem, or flying flags half-mast after the discovery of hundreds of buried bodies of the children who attended residential schools. For Indigenous people to be recognized and treated as equals in the eyes of the government, action must be taken and governments must be held accountable, especially by non-Indigenous Canadians- because if it doesn’t, we will only see these horrible acts like medical discrimination, eugenics, and genocide, become a bigger issue than we could have ever imagined.

No comments:

Post a Comment